About the Music

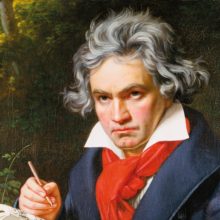

Ludwig van Beethoven Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43

Composed: 1801

Premiered: 1801 at the Burgtheater in Vienna. Premiered in New York at the Park Theatre in 1808, one of the first full length works by Beethoven to be performed in the United States

Length: c. 5 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Tune in to the Music: Beethoven: Overture to the Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43 by Wiener Philharmoniker, conducted by Leonard Bernstein in Berlin

What to listen for: The Overture is full of energy from beginning to end, unfolding in an exhilarating and vigorous musique parlante – music that speaks eloquently without words. It sets the scene for the ballet to follow, which depicts parts of the Prometheus myth.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

“… music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy, the wine which inspires one to new generative processes, and I am the Bacchus who presses out this glorious wine for mankind and makes them spiritually drunken.”- L. v. Beethoven

About the Music

In 1800, Beethoven was 29 years old and facing a major commission to write his first work for the stage, a ballet based on the myth of Prometheus. The Italian composer and dancer Salvatore Viganò was originally tasked with presenting the work to the Viennese Archduchess Maria Theresa. While Viganò usually composed his own music for his performances, he felt this performance was far too important and asked Beethoven to compose instead. The complete music for the ballet consisted of an overture, introduction, and sixteen numbers, but, since the overture was the only one Beethoven had written at that time, he often performed it separately to open concerts of his music.

Although the original text and choreography of the ballet is lost, Beethoven’s particular rendering of the story of Prometheus remains. It tells of Prometheus, an exalted spirit who, finding the people of the time ignorant, creates statues of a man and a woman to bring to life. He then takes the statues to Mount Parnassus where various characters of antiquity instruct them in knowledge, scholarship, and the arts, thus lifting humanity. To Beethoven’s disappointment, the scenario omitted the more dramatic elements of the Prometheus story, in which Zeus punished Prometheus for elevating man to the status of the gods Prometheus is chained to a rock. An eagle visits him daily to eat his endlessly-regenerating liver.

The overture appeared in print in 1804, and remains the only part of the ballet that is frequently performed. The Prometheus Overture unfolds as an exhilarating and vigorous musical ride. One of the driving forces behind Beethoven’s approach to Prometheus was his admiration of Haydn’s oratorio, The Creation (1798). Beethoven was striving for a secular equivalent while also creating something new that transcended oratorio, opera, and the symphony, elevated by musique parlante – music that speaks eloquently without words.

The Creatures of Prometheus ballet ran successfully for 28 performances. Nevertheless, one influential critic found Beethoven’s music to be “too intellectually demanding” for ballet, and not suitable for dancing. Beethoven’s naturally rebellious spirit could be felt in the music, and no further commissions for ballets ever came his way. Today, the work is increasingly recognised as pivotal in Beethoven’s evolving style, its heroic spirit paving the way for the Eroica Symphony, No. 3 (1803), his opera Fidelio (1805), and the Violin Concerto (1806).

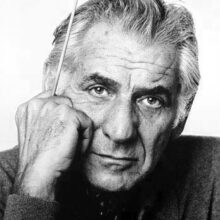

Leonard Bernstein Serenade (after Plato’s Symposium) Noah Bendix-Balgley, violin

Composed: August 1954

Premiered: Teatro La Fenice in Venice, September 1954

Dedicated to: Serge and Natalie Koussevitzky

Length: 30 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Tune in to the Music: Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade based on Plato’s “Symposium”, performed by Midori and the WDR Symphony Orchestra , conducted by Constantinos Carydis at the Kölner Philharmonie.

What to listen for: The fifth movement, Socrates; Alcibiades, depicts Socrates’ “profundity of love”, and its gravitas sets it off from the other movements. Bernstein wrote: “If there is a hint of jazz in the celebration, I hope it will not be taken as anachronistic Greek party-music, but rather the natural expression of a contemporary American composer imbued with the spirit of that timeless dinner party.”

“Love is simply the name for the desire and pursuit of the whole.”

-Plato, The Symposium

Leonard Bernstein (August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990, Lawrence, Massachusetts) was exposed to music from the earliest age, although not in a formal way. In fact, his illustrious career as one of America’s foremost composers and conductors began by Iistening to the household radio and music on Friday nights at Congregation Mishkan Tefila in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Bernstein began teaching himself piano and music theory at age ten, and was soon clamoring for lessons. In the summers, the Bernstein family would go to their vacation home in Sharon, Massachusetts, where young Leonard conscripted all the neighborhood children to put on shows. He would often play entire operas or Beethoven symphonies with his younger sister.

Leonard Bernstein (August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990, Lawrence, Massachusetts) was exposed to music from the earliest age, although not in a formal way. In fact, his illustrious career as one of America’s foremost composers and conductors began by Iistening to the household radio and music on Friday nights at Congregation Mishkan Tefila in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Bernstein began teaching himself piano and music theory at age ten, and was soon clamoring for lessons. In the summers, the Bernstein family would go to their vacation home in Sharon, Massachusetts, where young Leonard conscripted all the neighborhood children to put on shows. He would often play entire operas or Beethoven symphonies with his younger sister.

Bernstein’s father was initially opposed to young Leonard’s interest in music and attempted to discourage his son’s interest by refusing to pay for his piano lessons. Leonard then took to giving lessons to young people in his neighborhood. Eventually the family supported his music education. In May 1932, Leonard attended his first orchestral concert with the Boston Pops Orchestra conducted by Arthur Fiedler. Bernstein recalled, “To me, in those days, the Pops was heaven itself … I thought … it was the supreme achievement of the human race.” Another strong musical influence was George Gershwin.

Bernstein attended Harvard University where he majored in music with a final year thesis titled “The Absorption of Race Elements into American Music” (1939; reproduced in his book Findings). One of Bernstein’s intellectual influences at Harvard was the aesthetics Professor David Prall, whose multidisciplinary outlook on the arts inspired Bernstein for the rest of his life. After Harvard, Bernstein enrolled at Curtis Institute of Music where he studied conducting with Fritz Reiner. Soon after, he moved to New York City where he worked as a musician and music teacher. In 1943 he made his debut as a conductor with the New York Philharmonic, stepping in at the last minute for the ill conductor. His performance and subsequent work propelled to instant worldwide fame.

Bernstein was the first American-born conductor to lead a major American symphony orchestra. He was music director of the New York Philharmonic and conducted the world’s major orchestras, generating a legacy of audio and video recordings. He shared and explored classical music on television with a mass audience in national and international broadcasts, including Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic.

Bernstein was the first American-born conductor to lead a major American symphony orchestra. He was music director of the New York Philharmonic and conducted the world’s major orchestras, generating a legacy of audio and video recordings. He shared and explored classical music on television with a mass audience in national and international broadcasts, including Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic.

A prolific and successful composer across multiple genres, Bernstein valued inclusion across every category of color, ethnicity, gender, and identity. For example, Bernstein and his friend Jerome Robbins expanded their ballet Fancy Free into the musical On the Town in 1944. The show broke major race barriers on Broadway: Japanese-American dancer Sono Osato was cast in a leading role; a multiracial cast danced as mixed race couples; and the orchestra was led by a Black concertmaster, Everett Lee, who eventually took over as music director of the show. Bernstein redefined the Broadway stage with his scores for the musicals Wonderful Town (1953), Candide (1956), and West Side Story (1957).

Bernstein worked in support of civil rights, protested against the Vietnam War, advocated for nuclear disarmament, raised money for HIV/AIDS research and awareness, and engaged in multiple international initiatives for human rights and world peace. He conducted Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony to mark the death of president John F. Kennedy, and in Israel at a concert, Hatikvah on Mt. Scopus, after the Six-Day War. At the end of his life, Bernstein conducted a performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in Berlin to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall.

About the Music

During the summer of 1954, Bernstein focused on two major compositions: his operetta-styled musical Candide, and a new orchestral piece featuring solo violin. Completed that summer, this violin concerto became the five-movement Serenade, satisfying two commitments: a much delayed commission for the Koussevitzky Foundation (1951), and the promise of a piece for violin and orchestra for his friend, the eminent violinist, Isaac Stern. Composed in less than a year from late 1953 through August 1954, Bernstein dedicated the Serenade to the memory of his mentor, Serge Koussevitzky, and to Koussevitzky’s first wife, Natalie. Scored for solo violin, harp, string orchestra, and percussion, Serenade remains one of Bernstein’s most lyrical orchestral works.

Bernstein composed Serenade after a rereading of Plato’s The Symposium, an ancient text that explores the nature and purpose of love. The music introduces new ideas about love through expansion or refinement of earlier elements in the composition. Longtime Bernstein music advisor Jack Gottlieb called this process of evolution and transformation, “melodic concatenation”.

Bernstein composed Serenade after a rereading of Plato’s The Symposium, an ancient text that explores the nature and purpose of love. The music introduces new ideas about love through expansion or refinement of earlier elements in the composition. Longtime Bernstein music advisor Jack Gottlieb called this process of evolution and transformation, “melodic concatenation”.

Berenstein’s Serenade owes much to Igor Stravinsky who, in scores such as Oedipus Rex (1927), Apollon Musagète (1928), Persephone (1933), and Orpheus (1947), demonstrated an interest in Greek archetypes and themes from Classical literature and mythology. In an interview with his future biographer Humphrey Burton in 1986, Bernstein remarked that the piece was “originally called Symposium [but] I was dissuaded from that title because people said it sounded so academic. I now regret that. I wish I had retained the title so people would know what it is based on… It’s one of Plato’s shortest dialogues and it’s on the subject of love. It’s seven speeches, at a banquet, after-dinner speeches so to speak. By Aristophanes, by Agathon, by Socrates and himself… it’s really a love piece.”

On August 8, 1954, the day after completing his score, Bernstein wrote the following descriptions for each movement as a suggested series of “guideposts” for the listener:

- Phaedrus; Pausanias (Lento; Allegro marcato). Phaedrus opens the symposium with a lyrical oration in praise of Eros, the god of love. (Fugato, begun by the solo violin.) Pausanias continues by describing the duality of the lover as compared with the beloved. This is expressed in a classical sonata-allegro, based on the material of the opening fugato.

- Aristophanes (Allegretto). Aristophanes does not play the role of clown in this dialogue, but instead that of the bedtime-storyteller, invoking the fairy-tale mythology of love. The atmosphere is one of quiet charm. [Aristophanes sees love as satisfying a basic human need. Much of the musical material derives from the grace-note theme of the first movement. The middle section of this movement incorporates a melody for the lower strings (marked “singing”) played in close canon.

- Eryximachus (Presto). The physician speaks of bodily harmony as a scientific model for the workings of love-patterns. This is an extremely short fugato-scherzo, born of a blend of mystery and humor. [This section contains music that corresponds thematically to the canon of the previous movement, Aristophanes]

- Agathon (Adagio). Perhaps the most moving speech of the dialogue, Agathon’s panegyric embraces all aspects of love’s powers, charms and functions. This movement is a simple three-part song.

- Socrates; Alcibiades (Molto tenuto; Allegro molto vivace). Socrates describes his visit to the seer Diotima, quoting her speech on the demonology of love. Love as a daemon is Socrates’ image for the profundity of love; and his seniority adds to the feeling of didactic soberness in an otherwise pleasant and convivial after-dinner discussion. This is a slow introduction of greater weight than any of the preceding movements, and serves as a highly developed reprise of the middle section of the Agathon movement, thus suggesting a hidden sonata-form. The famous interruption by Alcibiades and his band of drunken revelers ushers in the Allegro, which is an extended rondo ranging in spirit from agitation through jig-like dance music to joyful celebration. If there is a hint of jazz in the celebration, I hope it will not be taken as anachronistic Greek party-music, but rather the natural expression of a contemporary American composer imbued with the spirit of that timeless dinner party.

Also incorporated into Serenade are several quotations from some of Bernstein’s solo piano pieces which he named “Five Anniversaries,” short works dedicated to close friends as birthday gifts or memorial tributes. Weaving these musically intimate compositions (in particular: For Elizabeth Rudolf, For Lukas Foss, For Elizabeth B. Ehrman, and For Sandy Gelhorn) into the fabric of this concerto seems particularly appropriate, given its focus on the nature of human relationships.

Despite its serious intentions, Serenade is as diverting as it is illuminating. Biographer Burton observed that the work, “can also be perceived as a portrait of Bernstein himself: grand and noble in the first movement, childlike in the second, boisterous and playful in the third, serenely calm and tender in the fourth, a doom-laden prophet, and then a jazzy iconoclast in the finale.”

Serenade has become a staple of the violin repertoire, with such notable soloists performing the work as Gidon Kremer, Joshua Bell, and Midori. This remarkable piece confirms Bernstein’s authority as a composer of symphonic music.

Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93

Composed: 1812

Premiered: February 27, 1814, at a concert in the Redoutensaal, Vienna

Length: c. 26 minutes

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Tune in to the Music: Beethoven: 8. Sinfonie ∙ hr-Sinfonieorchester ∙ Paavo Järvi

What to Listen For: Artistic Director and Conductor José-Luis Novo notes, “the explosion of happiness we hear at the very beginning of this piece is a very unique way to start a symphony for Beethoven, and it is going to set the mood for most of the work. And of course, the metronome-like effect in the second movement with the mechanical rhythm suggests the “tick-tock” effect of the first metronomes, recently invented at the time of this composition and used by Beethoven to great effect in later compositions.”

Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony was composed in 1812. He fondly referred to it as “my little Symphony in F”. In fact, Beethoven quite liked his Eighth, although when it first premiered it wasn’t nearly as popular as others, such as his Seventh or Wellington’s Victory.

The Eighth Symphony is generally light-hearted, with musical jokes running throughout. Beethoven changed the minuet and trio movements common in late eighteenth-century symphonies into scherzos, which became central to the symphonies of Beethoven and later composers. Scherzos are, by definition, humorous. They thwart conventions and are intended to delight the player and the audience. In the Eighth Symphony, Beethoven’s scherzando attitude encompasses all four movements of the symphony. As with various other Beethoven works, the symphony deviates from Classical tradition in making the last movement the weightiest of the four instead of the first.

Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony was composed in 1812. The piece is generally light-hearted, with musical jokes running throughout. Beethoven changed the Minuet and Trio movements common in late eighteenth-century symphonies into Scherzos, which became central to the symphonies of Beethoven and later composers. Scherzos are, by definition, humorous. They thwart conventions and are intended to delight the player and the audience. In the Eighth Symphony, Beethoven expanded the scherzo character to encompass the entire symphony. As with various other Beethoven works, the symphony deviates from Classical tradition in making the last movement the weightiest of the four.

Alberto Ginastera Four Dances from Estancia, Op. 8a

Composed: 1941

Premiered: Teatro Coloacuten, Buenos Aires, 1943

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Tune in to the Music: Ginastera: Danzas del Ballet »Estancia« ∙ hr-Sinfonieorchester ∙ Andrés Orozco-Estrada

What to Listen For: The final movement, “Malambo”, represents a contest amongst the macho gauchos, and takes its title from a dance that has long figured in a competition among Argentine cowboys. As the contest develops, the music becomes increasingly complex, gains momentum, and becomes louder as the constant eighth note, finally ending in a fantastic climax.

Alberto Ginastera (April 11, 1916 Buenos Aires, Argentina -June 25, 1983 Geneva, Switzerland) achieved great fame as Argentina’s leading nationalist composer in the post World War II era. Ginastera is admired for blending of indigenous music with European techniques, a focus of all his works during the early years of his career. Several of the fifty-five works he composed stand as landmarks of Latin-American symphonic artistic creation and have earned him a place – together with the Mexican Carlos Chávez and the Brazilian Heitor Villa-Lobos – among the greatest Latin composers of the twentieth century. As well as two concertos for piano, one for violin, two for cello, and one for harp, he wrote two operas, ballet music, orchestral music, chamber music and a dozen works for solo piano. Masterworks IV includes a performance of Estancia, originally written as a ballet but later transformed into a four-movement symphonic suite.

Alberto Ginastera (April 11, 1916 Buenos Aires, Argentina -June 25, 1983 Geneva, Switzerland) achieved great fame as Argentina’s leading nationalist composer in the post World War II era. Ginastera is admired for blending of indigenous music with European techniques, a focus of all his works during the early years of his career. Several of the fifty-five works he composed stand as landmarks of Latin-American symphonic artistic creation and have earned him a place – together with the Mexican Carlos Chávez and the Brazilian Heitor Villa-Lobos – among the greatest Latin composers of the twentieth century. As well as two concertos for piano, one for violin, two for cello, and one for harp, he wrote two operas, ballet music, orchestral music, chamber music and a dozen works for solo piano. Masterworks IV includes a performance of Estancia, originally written as a ballet but later transformed into a four-movement symphonic suite.

About the Music

Estancia is an orchestral suite and one-act ballet by Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera, written when he was twenty-five. References to gaucho literature, rural folk dances, and urban concert music evoke images of the diverse landscape of the composer’s homeland. It was originally commissioned by the American Ballet Caravan in 1941, but that show wasn’t realized until 1952. Ginastera premiered a four-movement orchestral form in 1943.

The Estancia ballet, somewhat more than half an hour in length, takes inspiration from the epic poem Martin Fierro by José Hernández, which borrowed its rhythmic structure from traditional balladry. It tells the story of a city boy in love with a rancher’s daughter. At first, the love affair is one-sided, as the girl finds the boy spineless, at least in comparison with the intrepid gauchos. By the final scene, however, the hero has won the girl’s heart by outdancing the gauchos in a traditional contest on their own terrain.

The four movements are rich in rhythms and tunes from Argentinian folklore. A single day on a large ranch tells of longing, romance, and love of a young couple, the exuberance of the macho gauchos, and the beauty of the pampas landscape. Each movement is characterized by a distinct rhythm:

“Los trabajadores agricolas” (The Land Workers features a vigorous rhythm – but virtually no melody – evoking South American dance rhythms. Subtle changes in the basic rhythm create variety and tension.

“Danza del trigo” (Dance of the Wheat)evokes the serenity of pampas fading into the horizon. A traditional Hispanic melody provides a sharp contrast to the percussion in the preceding movement.“Los peones de hacienda” (The cattlemen) is a heavy-footed stomp drawn from traditional Latin rhythms.

“Danza final (Malambo)” (The final dance) is a machismo dance with energetic steps, starting quietly but becoming wilder and faster until the climax.